The Future of Online Dating Will Be Mostly Offline

@notbenyam

February 2025

(23 days ago)

I’m currently prototyping an offline-first dating service called Bind. I share my thought process on ideating an approach to building in a notoriously difficult space.After some deliberation, as of Feb ’25, I have decided to not pursue this project. I walk through my thinking on the future of online dating below.

I’ve become very curious about what the future of online dating will look like. This makes sense given that I’m a single male in my mid-20s who hasn’t had a great time on dating apps (for various reasons). I have an interest in understanding the problem & finding an optimal solution.

In algorithm analysis, we constantly ask ourselves “is this the best we can do?”. We get a deep theoretical understanding of the problem, theorize an optimal performance given the constraints (not yet knowing the exact solution), then work towards a concrete solution achieving that performance.

We also aim to identify solutions that cannot exist, or may appear to be possible, but are impossible for one reason or another. Above all, we never settle for a solution that is “good enough”.

In this case, the problem is that of finding a highly compatible longterm partner. The best (online) solution for that today is Hinge (maybe Bumble, not Tinder). We will try to understand what comes after these services (2025 & beyond), given the condition & desire of users today.

Before we continue (since it is relevant), this is what I look like:

Benyam Ephrem, June 2024 (colorized).

Prior Art

“Broken” vs Endemic

When people say “online dating today is broken,” they often aren’t very clear on “what” is broken. To create a better solution, it’s important we draw a distinction between problems created within online dating services, & problems that arise from the very nature of how humans make mating choices.

The nature of a problem is immutable. If all complaints we can generate reduce simply to human nature & the mating decision process, we have nothing further to act on or investigate. This would mean we are at an equilibrium (albeit a very uncomfortable one).

We will draw a line between dissatisfaction:

- endemic to human mating in any context

- arising from the online dating experience (making highly selective mating choices in a context of little information, an online profile)

- arising from other sources (causes we may or may not be able to change)

But before we continue, we need to first understand the problem we are trying to solve.

Modeling the Problem

Going for a Stroll

Imagine it’s a sunny weekend and you decide to go for a stroll through a local farmer’s market nearby. You may pass 100-300 people if you are out for a few hours. Couples, friends, families of all ages & races — all at different points in life, with different interests, with different personalities.

When you return home, a friend poses you a challenge: “Of all the people you saw today who may be single, could you guess who would make good romantic partners with whom?”. Essentially, could you act as a matchmaker to predict the largest and most correct set of couples-to-be (ideally better than random pairings taking into account basic compatibility measures)?

This would be pretty hard. You could eyeball it, pairing people of similar age, physical attractiveness, similar interests (”they both looked outdoorsy”), etc — all taking into account rudimentary relationship science of what each gender & orientation prefers in their partners. And you’d get it right sometimes.

The challenge is that there is a lot that you do not know about who you are pairing, or the emergent properties of pairings you are considering. People are obviously very complex creatures. You’d also need to be considerate of everyone equally, ensuring that no one gets less consideration than anyone else so you can create as many pairings as possible.

What if your friend instead asked you about your immediate friends and social circle? Would you be able to do it? Probably. You may naturally have been speculating on who would be a good match for who all along anyway. This would be much more approachable.

What if instead, you had a database of 23,000,000 people? Roughly 65% male, and 35% female[1]. 1,400,000 of them paying you to matchmake for them. This was Hinge’s job in 2023.

This would be impossible for one person, or even a team of people to reason through. You’d need to formalize the problem and develop an algorithm to solve it.

The Dating “Marketplace”

Mate selection operates as a two-sided competitive market. It’s a bit clinical to use the term “market” here, but being precise will be important to us framing the problem correctly. It will give us tools to understand the nature of platforms & see into the future (more on this later).

Every individual has a goal, and a strategy to achieve that goal. Strategy can be consciously known to the individual, or completely subconscious.

Any dating service has to decide how “fair” it will be in its matching process, since it must help users move towards their goals. While not necessarily a zero sum game, one user’s gain may lead to another user’s lost opportunity.

A solution that is globally “fair” (one that aims to maximize the surface area under the “user satisfaction curve”) will not be a solution where every individual user is maximally satisfied.

Even in a maximally “fair” service, as in any competitive two-sided market, there will always be some portion of individuals who, given their strategy:

- completely fail to achieve their goals

- partially fail to achieve their goals

- partially succeed in achieving their goals

- completely succeed in achieving their goals

Mate choice, by design, is not fair. Evolution has encoded within us the drive to favor some as mates, and disfavor others. Subtleties as minor as a person’s voice, gait, posture — can all cause us to disqualify a partner.

No matter how fair or unfair the design of a dating service, this core of selectivity will exist. There will always be a set of individuals who cannot successfully be matched, and subsequently dissatisfied in not meeting their goals.

According to Pew Research, over 50% of online dating users report somewhat negative, to very negative, experiences dating online[2]. Is this necessarily an actual problem that can be addressed? Is online dating broken? Or are online platforms only surfacing data that has never been available to us before about human selectivity. (it’s a bit of everything)

People with a very positive experience are likely easy to match (many other users would select them as a partner). People with a very negative experience are likely very difficult to match (for whatever reason). There’s likely not much we can do to markedly change outcomes on these tail ends.

What should be of most interest to us is the middle of the distribution. Partially satisfied users and partially dissatisfied users who could experience better matchmaking (or a better user experience). This is where there is opportunity to reshape user success.

The Present

To understand where we’re going, it’s important to understand where we’re currently at. If you decided that you wanted to find your partner online in 2025, what choices would you have?

The Match Group Machine

Tinder, Bumble, & Hinge are the largest online dating services in the U.S., constituting ~85% of the online dating market. Marketshare breaks down roughly like this (founding date added for context):

- Tinder (~40% — f. 2012)

- Bumble (~25% — f. 2014)

- Hinge (~20% — f. 2011)

- Others:

- Plenty of Fish (POF) (~4% — f. 2003)

- OkCupid (~4% — f. 2003)

- Match.com (~3% — f. 1995)

- Grindr (~3% — f. 2009)

- The League (~2% — f. 2014)

- BLK (~1% — f. 2017)

- BlackPeopleMeet (~1% — f. 2002)

- ... and the list goes on

Only Bumble & Grindr remain independent & are not owned by Match Group. Match Group controls ~70% of the U.S. online dating market.

Is Match Group a monopoly? Is there anything anti-competitive going on here? According to the FTC website[3]:

While Match Group may hold dominant marketshare & controls almost all alternative products people may turn to, they don’t have to engage in much anti-competitive conduct to maintain their marketshare.

The difficulties in bootstrapping a new dating service from scratch are naturally insurmountable. The nature of marketplaces protect them.

The Importance of Options

One of the most important characteristics of any market is abundance of choice. Nobel prize winning economist Alvin E. Roth calls this property “thickness”. The more options, the thicker the market.

You’ve likely heard the term “liquidity” in financial markets. Usually we think of it in one direction, the ease of selling an asset to convert it back into fungible currency. But it goes both ways, those wanting to buy a certain allotment hope for ease in completing their transaction as well.

Larry Harris in “Trading & Exchanges” offers a simple definition[4]:

Access to options in a market is so important that market makers (market participants that “make a market” by always offering to buy or sell an asset, even in the absence of “regular” buyer or sellers providing price information) are willing to pay brokers for orders to be routed to them (called “payment for order flow”, PFOF).

Options are highly valuable & competed for, because they allow market participants to have more opportunities to meet their goals (at lower cost), reducing difficulty in solving the search problem.

Fragmentation is the enemy of market density. It divides trading options amongst various separate databases (and even completely separate geographic locations), increasing difficulty in solving the search problem.

Markets that cannot gain enough momentum either fail, or end up merging into a larger entity to gain the density needed to solve the search problem.

The Opportunity Window

So what does this have to do with online dating? The largest online dating platforms hold the most options, and the services with the most dating options will create a natural pull for users to transition to them to better solve their search problem.

Markets usually progress in “windows of opportunity”, some “big picture” change happens (a technological breakthrough, a new social norm, etc), then there exists fertile ground for certain kinds of companies to take root & grow. Then after 2, 3, 4 years — the window slowly closes, competition means:

- customers have many choices, the bar on features goes higher

- cost of entry to reach feature parity goes up

- employees become harder to hire

- capital becomes harder to raise

- crafting unique marketing messaging becomes harder

In the early 2010s (recall Tinder was founded in 2012, Hinge 2011, Bumble 2014), mobile phones presented such a window. Since people took their phone everywhere, users could join & be active on services in record numbers.

Tinder popularized the “double opt-in” model of matching where both individuals in a match had to mutually “like” each other before a match was made. Most of the 2010s would be various startups building different permutations of this model, in different geographies, for different demographics.

The longer this profile → double opt-in match → message experince existed, the less likely it was that a new service could appear unless it was markedly different. Even then, by the late 2010s, the power law had already taken hold. The market started to calcify.

The final result, with the dust fully settled from the 2010s, was Hinge, Bumble, & Tinder owning 85% of the U.S. online dating market.

Credit Cards in the 1960s

A similar industry shakeout occurred in the U.S. credit card industry in the late 1960s.

Before credit cards, payments would either be done by cash or check. This presented issues for merchants because they would have to take on the credit risk of each of their customers directly. If a customer provided a check that bounced, the merchant risked losing the payment.

Credit card companies would take on the payment risk of each customer directly, extending a credit line to them. The credit card company would guarantee payments to merchants for a small “interchange fee” (usually 1-3%). The customer would become indebited to the credit card company, & later pay down their account.

Diners Club (f. 1950) was the first independent payment card company in the world, pioneering this charge card model. They both issued their cards & operated as a payment network. They partnered directly with restaurants, hotels, travel agencies, & entertainment venues to process payments.

The 1960s saw the emergence of general-purpose credit cards, as well as the rise of competing card networks like Master Charge (now Mastercard), BankAmericard (now Visa), & American Express (f. 1850, but released their own charge card).

Payment networks experienced the same runaway consolidation that we see in other matching markets. The more merchant banks a payment network partnered with, the more merchants accepted their payments, the more valuable a card became to cardholders (you could pay in more places with the same card).

By 2023, marketshare in the U.S. by purchase volume[6] looked like this:

- Visa (~52.2% — f. 1958)

- Mastercard (~24.13% — f. 1966)

- American Express (~19.78% — charge card, f. 1958)

- Discover (~3.87% — f. 1985)

No major payment networks aside from the handful started around this time exist today.

Evolution of Desire

Before we look at the problems that bringing dating online creates, it’s essential we touch on (the touchy subject of) what men & women really want in a partner. We won’t go too deep down the evolutionary psychology rabbit hole, but we actually have well-researched, definitive answers to this question.

It’s important to note that these desires act in complex combination with one another. Imagine a painter’s palette, with distinct colors that are mixed to form new colors. Regardless of everyone having a messy palette when finished painting, we all still start with the same colors (the same core biological drives).

Desires differ greatly between when we are looking for a short-term vs. long-term (or life) partner. In ”The Evolution of Desire“ David M. Buss mentions[7]:

It’s easy to overstate the evolutionary lens. We will only use it as a foundational tool for later discussion, not as our total understanding.

What Men Want

Much of male attraction is physically based. Buss lists the attributes men most desire in women as youth, physical beauty, body shape, and chastity & fidelity.

The evolutionary explanation is that men use these easily observable cues to quickly judge fertility. Should they commit their resources to a mate, they must ensure their partner has strong reproductive potential.

Chastity & fidelity are important for the guarantee of paternity. Should a man commit his resources to a partner to raise young, he has to make sure they are his and not another’s. Thus, purity, knowing that your partner is your & yours alone is paramount.

Buss says:

As a man I can empirically confirm that physical attractiveness is a strong component of male attraction. Within 1-2 seconds of entering a room, a bus ride home, etc — consciously or subconsciously, men will scan their surroundings for attractive women, determine who is most interesting, & keep an index in the back of their mind. Sometimes it happens in less than a second. Men almost always know who the most attractive women are in a room, whether they are aware of this process or not.

It’s very easy to oversimplify this and assume men only want the most physically attractive women. A host of other intangible factors like intelligence, agreeableness, emotional stability, and personality also play a key role, altering perception of physical attractiveness.

In a 2023 study of 201 heterosexual couples in Alberta, Canada, researchers at Burman University found objective physical attractiveness (OPA) was weakly correlated with (partner assessed) percieved physical attractiveness (PPA), underscoring the role of subjective perception and non-physical factors in attraction between partners[8].

There is conflicting research on whether percieved physical attractiveness between partners actually predicts relationship quality. In a 2008 study amongst 82 newlyweds, researchers at the University of Tennessee found that there was no correlation between either partner’s physical attractiveness and rated relationship quality[9].

The 2023 Canadian study mentioned before disagrees, finding that the PPA of women was more strongly linked to both their own and their male partner’s relational satisfaction compared to the PPA of men (men’s percieved physical attractiveness influenced their partner’s relationship quality to a lesser extent — with men’s self-esteem and social skills being major predictors of RQ). 101 couples in the study were married or cohabiting.

What Women Want

For women physical attractiveness in a partner is important, but the capability to provision resources (social, financial, etc) and satisfy emotional needs take a central role. Buss says:

Buss lists the attributes women most desire in men as:

- Resource Potential

- Social Status

- Age (2-3 years older)

- Ambition and Industriousness

- Dependability and Stability

- Intelligence

- Compatibility

- Size, Strength, V-Shaped Torso

- Good Health, Symmetry, and Masculinity

- Love, Kindness, and Commitment

Despite having a longer preference list than men, I could not locate any research studies verifying if women had a higher variance in what they desire in their partners than men. In a 2022 podcast with Lex Fridman, Buss mentions[10]:

Women value physical attractiveness in a partner more than popular culture would have us assume (though I think in the past few years public opinion has caught up a bit).

In a 2017 study by Fugere et al[11], researchers found that a minimum level of physical attractiveness was a necessity in mate selection for both women & their mothers. The study demonstrated that attractive and moderately attractive men were consistently preferred over unattractive men, even when unattractive men had the most desirable personality traits.

The study also found that women and their mothers associated attractiveness with positive personality characteristics, suggesting an implicit bias in mate selection. While women placed a stronger emphasis on attractiveness than their mothers, mothers still required a minimum level of attractiveness before prioritizing other traits. These findings suggest that when individuals claim to prioritize personality over looks, they may implicitly assume a potential mate already meets a basic attractiveness threshold.

Now with a very high-level understanding of what each gender desires in a partner, we can look at problems created when these desires are pursued in a purely online context.

New Problems

There is no setting, online or offline, in which dating is not difficult. When selective pressure meets selective pressure in such a delicate part of our lives, there is bound to be heartbreak & disappointment.

But there are some problems unique to profile-based online dating that are introduced by the medium itself. We will look at them now.

Losing Information

The amount of information an online dating service collects from it’s users during onboarding will always be at contention with how large the userbase can grow. You cannot scale to a userbase of 20,000,000+ users (within a reasonable amount of years, within reasonable cost) with 100+ question onboarding surveys.

You must get to a critical mass within any given geographic area to produce matches. Every user that joins increases the likelihood that the next user will have a match somewhere in the dating pool. So you must decide what information you absolutely need, and what information you can do without.

Hinge was designed to be light & fun to use, accepting only 6 photos and 3 prompts from users. This was an intentional design decision. The founder of Hinge Justin McLeod says in a 2024 interview[12]:

While well intentioned in the early 2010s (and the correct product design decision given the market), this would prove to be an insidious design pattern that would permiate the next decade of mobile dating.

While some users would write thoughtful prompts that allow the service to learn more about them, many low-effort profiles (often from appealing users) contained mindnumbingly simple-minded prompts, a few examples (from personal observation):

- “I bet you can’t” → “beat me at mario kart.”

- “Typical Sunday” → “the local farmer’s market.”

- “What I order for the table” → “aperol spritz.”

- “The best way to ask me out is by” → “asking me out.”

- “Change my mind about” → “men.”

Recommendation Woes

To create a formal algorithm, services have to model users as a set of discrete pieces of information. This is a very lossy conversion, with no ideal continuous data flywheel for the internal datamodel to self-correct to truly learn who the person is.

YouTube generates remarkable recommendations based on observing user watch time. A home feed is generated, with predicted watch times per video, then YouTube observes the user’s actual watch time (if they even click on a video) to learn how to improve the model[13]. YouTube videos are hotbeds for data extraction (image, audio, text), and the wide array of topics on the service allows for a very rich model to be trained.

Instagram promoted product recommendations have been similarly exceptional in recent years, with the shop feature becoming a first-class tab in the app (later replaced by the “Reels” tab).

The consistent pattern — lots of data, lots of user activity, lots of direct feedback on user success. For YouTube, success is a user watching a lot of a video of relevance to them, for Instagram it is a user purchasing a product of relevance to them. These are observable & easy to collect data on. So the recommendation algorithms get very good.

Despite having enough data to do basic matchmaking, most online services will be missing a lot of information core to creating an exceptional algorithm to matchmake amongst millions of users.

There is only so much information you can extract about someone from 6 photos, 3 prompts, various biographical information, and dating preferences. Though, it’s likely “good enough” to make matches happen (since people of similar physical attractiveness, intelligence, and personality are usually attracted to each other) — services never get to truly “know the real you”.

Collecting data on how dates went is difficult. Users rarely check the app & aren’t very willing to fill out extensive surveys on how dates went. Many male (or female) users may never even go on a single date. So the most valuable data event happens infrequently for the users who need the most tailored matchmaking (those harder to match).

But now you might say “But services do have data on who you like, it comes from the feed. You can recommend more of whoever the user liked.” This goes hand-in-hand with the next problem, hyperselectivity.

Exacerbating Hyperselectivity

Physical attractiveness is the most important factor when dating online. This is also the case in real life, but to a far lesser degree. There is a lot of information you can communicate in real life that you can never do so digitally.

Left to our own devices, scrolling through endless profiles from the comfort of our homes, we can be remarkably selective — perhaps too selective. This detachment from reality allows us to maintain impossibly high standards, far more stringent than we'd apply in real-life encounters.

I could not find a reputable study on the distribution of linger time per profile, but from personal experience and observing male friends, it is less than a few seconds. Only enough time to see the first photo and bio information.

Women are markedly more selective than men (this would be the case online & offline). In a 2019 study by Brecht Neyt et al[14], researchers conducted a field experiment on Tinder finding that male users swiped right (liked profiles) 61.9% of the time, whereas female users only swiped right 4.5% of the time.

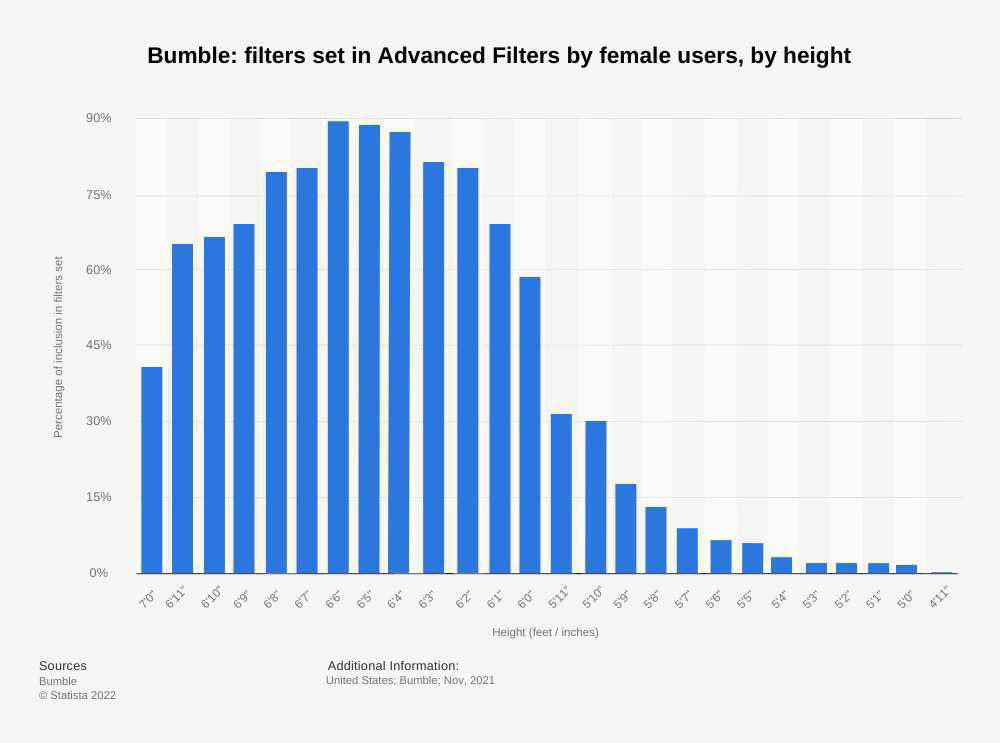

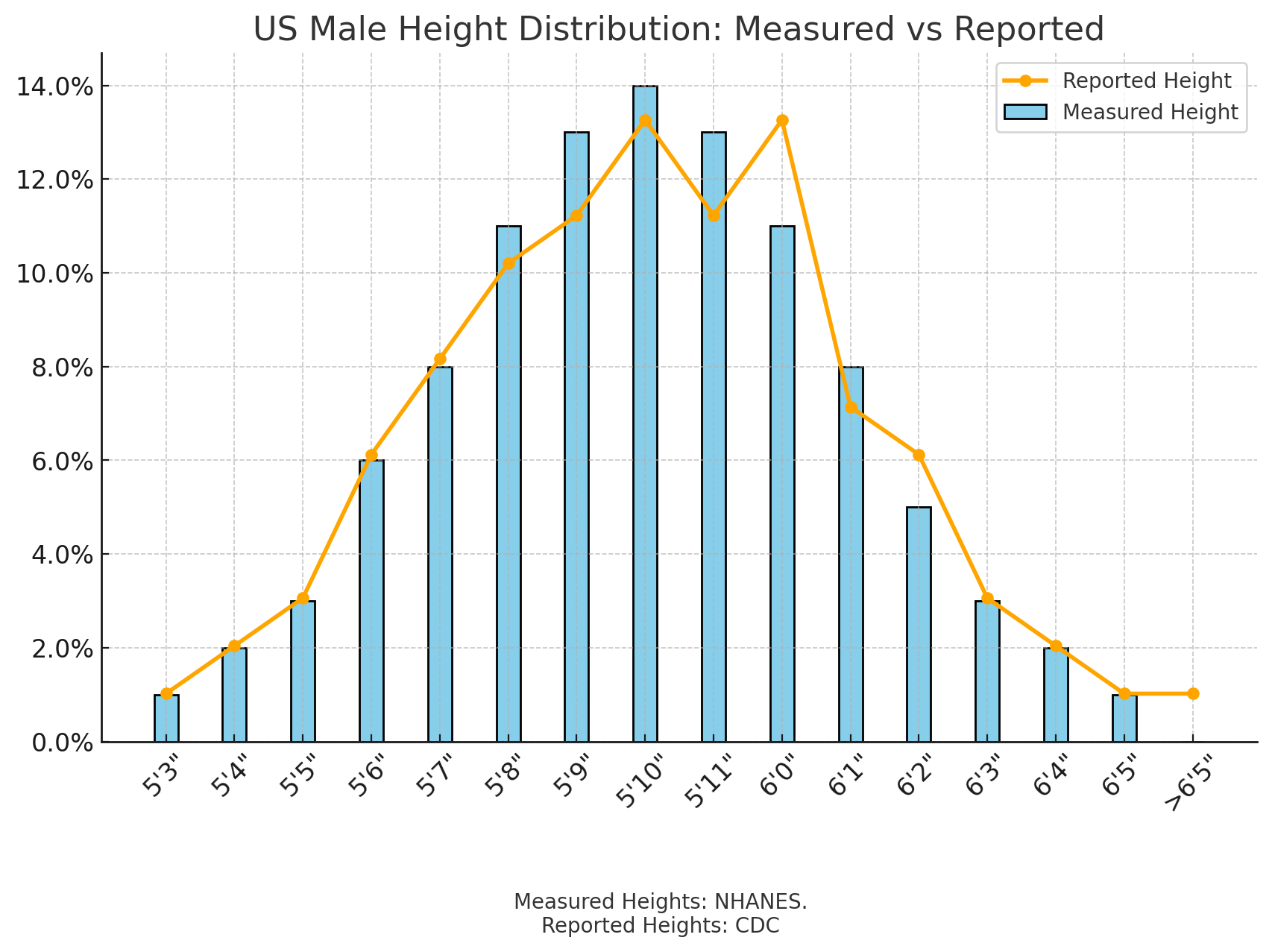

A 2022 survey by Statista[15] on Bumble users found that while over 60% of women were interested in dating men over 6 feet tall, only 15% of women were interested in men shorter than 5’8”. This is in stark contrast to the actual distribution of male height in the general population, where ~85% of men are below 6’ tall (male height distribution for the US is shown in the 2nd image below).

Bumble height preferences among female users, 2022.

Male height distribution in the US (~early 2020s).

While I could not find research on the average physical attractiveness of profiles men swipe on, I imagine it is even more particular than women’s preferences.

In reality, compatability is rarely a checklist (aside from avoiding fundamental incompatibilities like different timelines for having children, agreeing on religion for the kids, etc). We’re all capable of being delightfully surprised on who we’d hit it off with.

When you have little context on who you’re swiping on, you risk overlooking countless meaningful connections with people who, despite not fitting an idealized checklist, could have been wonderful partners.

The convenience of profile-based dating has paradoxically made us less open to the beautiful imperfections and surprising chemistry that often spark genuine relationships.

Cold Intros

The most ideal way to meet a partner would be through just naturally living your life. Setups from your friends, connecting over shared interests, meeting at work, etc.

When you decide to create an organized service for people to meet a partner, you begin making matches in very disparate social circles. You get farther and farther from how actual relationships form.

The best kind of date is a “setup” from friends, where you are essentially “warm intro’d” to someone. Years of filtering & a distillation of qualities is implicit in the recommendation. Your friend group decided to continue to talk to this person after countless decision points where they could have abandoned the relationship.

Instead, online dating services (usually) match you with strangers, who you have no context on, then are asked to chat with over a DM. The courting process was never destined to initiate over a DM conversation.

We struggle to figure out what to say because we don’t know this person. Conversations fizzle out because it’s a high-effort process, and we’re one click away from hundreds of more options.

Impacts on Self-Esteem

Recall that online services have to generate matches among millions of users. The only way to do this is with some sort of algorithm.

That algorithm has to be fair, in the context of a selection process that is very unfair, and market dynamics that are unfavorable to users (~70% of online dating users are men, each gender is hyperselective beyond normal, etc).

Most (well designed) services will implement some form of stable matching algorithm to propose stable pairings (see Gale-Shapley). Services must infer who would prefer whom from:

- profile data (images, prompts)

- user activity (who likes who, total messages in DM, who messages first, etc)

- user feedback (feedback after dates, etc)

- other data that can be gathered from public sources (likely)

About a year into using Hinge in my final year of college I noticed that the attractiveness of profiles in my feed began to increase or decrease based on how “well” I was doing on the app (did I match with someone desirable and message back-and-forth recently? have I gone a month without a single match? etc).

Research on online dating’s impact on self-esteem and body image is mixed, but I personally found that in my early years of college my self-esteem was negatively impacted by using Tinder. This turns into a self-perpetuating cycle, where you present less confidently online (& in real life), which results in less dates, and so on.

The problem is when the algorithms and market dynamics skew against you, such that your true desirability in real life is not reflected in the profiles you are shown. If both modeled online & offline desirability were always perfectly the same, there would be no problem.

A lot of people would be greatly benefitted from not having an online dating algorithm continuously setting their self-esteem.

Misaligned Incentives

Charlie Munger is famously quoted as saying “Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome”. Digging through the transcript for his 1995 Harvard speech “The Psychology of Human Misjudgement,” it turns out he never said those exact words.

But of the “24 Standard Causes of Human Misjudgment” he would list, this was the first:

Online dating services have to make money, and ideally users would only pay when they are successful. The problem is that if users only paid when they got married, got into a relationship, or even when they went on a date — then the service would never make money.

Many users never see these success events, and if they were priced, they would be appalled at the price. Economist Alvin Roth calls a market “repugnant” when some people would like to participate, but others seek to prevent them from doing so, even if all transactions are voluntary.

Putting a price on relationships is a repugnant market setup that would not only be a weaker business model, but would struggle to see widespread social adoption, even if it would perfectly align incentives between users and the service.

So the next best thing is selling a software subscription. But the problem is that the customers with the highest lifetime value (LTV) are the ones who are the least successful. When users get what they want, the service loses 2 paying users at once.

So what is the outcome? A lot of paying users who get nothing (whether it is their fault or not). Some back-of-napkin reasoning:

- In 2023 Hinge had 23,000,000 users, ~1.3 million paying.

- Of paying users, about ~65% are men (men are 1.4x as likely to pay as women[2]).

- Of the 845,000 paying men, I would guess that <50% will ever go on a date, & maybe <20% will ever get into a relationship (there is no public data on these numbers).

- Assuming the average LTV of a paying Hinge user is ~$100 over a few years (drastically oversimplifying things, could be higher)

- 422,500 * $100 = $42.25 million in revenue that never results in any valuable outcome for users (not even a single date)

- 676,000 * $100 = $67.6 million in revenue that never results in a relationship

This only estimates the financial costs on unsuccessful usage, we can also estimate lost time.

On average users who use online dating do so for 6-10 hours a week[16]. So for the 422,500 male users in 2023 who never went on a date, 2,535,000-4,225,000 cumulative hours were lost scrolling a feed (105,625-175,854 cumulative days, or 289-481 cumulative years).

In a 2024 interview with Bloomberg, Founder of Bumble Whitney Wolfe Herd said:

The phrase “go online, to get offline” struck me as odd. It sounds like the same charter every dating app in the early 2010s started with, before failing to deliver on a future where we would be happier and more connected.

Unsuccessful recommendation algorithms & a hyperselective environment is what keeps otherwise matchable people on dating apps. To make users more successful, we need less technology in the loop, not more.

Overuse

One of my best friends had an old dog who passed away a few years ago named Zeke. Zeke always loved eating bananas. You could feed him banana after banana, and he would keep eating them.

Eventually my friend would have to slap my wrist and tell me to stop feeding him. He’d say, “Don’t you know, if you keep giving dogs food they’ll just keep eating it. They won’t stop by themselves”.

When you give people seemingly endless romantic options at the opening of an app, with one of the most powerful motivating forces within us driving usage (finding a romantic partner, 2nd to accumulating a lot of money), you’re going to get a lot of addicted users.

Dating app burnout is at an all-time high. While I couldn’t find reputable research on this, some informal surveys by various media outlets estimate that 70-80% of users are feeling some degree of burnout from years of dating app usage[18].

In the middle of 2024, dating app Hinge released “Your Turn Limits” to encourage users to keep conversations going[19]:

How did it take a company founded in 2011 over a decade to implement basic throttling in message inboxes? Well, incentives — in the 2010s companies were incentivized to deliver more matches than their competitors, not to minimize burnout.

Under mounting pressure to address a health crisis among users, companies like Apple released operating system level features like “Screen Time” (in 2018) to promote digital well-being and device usage awareness.

Very successful online dating services have the same responsibility. Now that burnout is becoming a real problem, there is incentive for companies to fix it to keep users from leaving their service.

The Future

Why Things Are Bad

Things don’t get better in the world until financial incentives arise for talented entrepreneurs to take on risk to create better solutions.

I think we are at a special point in time where people silently want something better, and are willing to pay for it. This was not as much the case in the late 2010s, it is very much more the case now in 2025.

The good opportunities arise silently. Usually no one shouts “I really want this company to exist, please go build this”. People tuned into a problem space & familiar with it’s characteristics notice the gaps.

In ”The Creative Act: A Way of Being”, Rick Rubin says[20]:

But there are barriers and risks that make this a particularly harder business to start & fund than run-of-the-mill B2B Saas.

No Soft Landing

There is no “soft landing” for an online (or offline) dating company. If you are a founder starting, or an investor considering funding, a company of this sort, your only paths to liquidity are generating profits (at the compromise of growth), or getting acquired in 4-8 years.

There is no ability to “merge” with other dating services (although it would be in the company & users’ best interest), since users trust you with sensitive personal data & their participation is tied to a heavy branding component.

Match Group has hacked this by creating a holding company that acquires online dating companies when they reach a critical point in growth. They then unlock synergies between their portfolio items without dissolving or merging individual brands.

On top of this, it is very expensive to get to a critical mass where the product is useful. Remember that every user that joins gives subsequent users a higher chance to find their best (or any) match.

So you will spend 2-3 years shoveling in & burning money, as Hinge, Bumble, & Tinder slowly drain your userbase away. Unless you are doing something markedly different to avoid this “brain drain”, it will slowly kill the business.

Weak Business Model

When you actually get users what they want, which is a loving partner, you lose 2 paying users. This should make us curious how other successful marketplaces handle this churn problem — one I can immediately think of is real estate sales.

Traditionally, real estate agents (in the US) earn a percentage (typically 5-6% total, split between buying and selling agents) of the final sale price of a home as a one-time fee, rather than charging clients a subscription for their time spent in the market.

The incentive is to get clients into a home as soon as possible, so they can earn their commission (ideally at a higher price). The counterbalance: clients have a budget, and referrals are a major component of how agents grow their business. So there is a counter-incentive to please clients by finding the best home possible, for the best price.

This model acknowledges and embraces the transactional nature of the business — success means facilitating a match that takes customers out of the market.

Online dating platforms cannot align incentives this perfectly. To do so would be to put a price on the formation of some of the most intimate relationships in our lives. As we discussed before, this would be a repugnant market setup many would protest (but many would happily participate in as well).

If you can’t directly make money off successfully pairing people, you only have a few other options:

- charge to join the service

- charge to actively use the service

- charge for premium features in the service

- charge for events (offline)

#1) Hinge tried to charge all users a flat subscription fee (no free tier) in 2018 and that was later reverted after it hurt growth (which is critical to a service’s value). This would be impractical for any large-scale general-purpose service, but may work for a smaller elite matchmaking service.

#2) Charging users a subscription for their time in a service is the best revenue model that has proven a practical success at scale today. This creates a massive waste amongst users who are difficult to match as they will be forced to pay for a service they are unlikely to find value in.

Because the drive to find a partner is so strong, downloading an app and filling out a profile is so easy, and the cost of subscription is not very high, this proves an accessible entry point for many users willing to pay.

#3) Features like “roses” & “super likes” in various services allow users to send “special” messages to users they are especially interested in. I could not find public data on what percentage of revenue comes from these features, but I predict these constitute <10-15% of total revenue.

The least successful users will likely be the ones using this feature, & it will likely be most ineffective on the most appealing users (unless they were going to be a match anyway). From reading online forums over the years, they seem to be a waste of money for most users.

#4) Charging for events can work, but will never grow into a material revenue source (enough to build an investment-grade service). Event businesses can reach single digit millions in revenue, but are very difficult to scale beyond that.

Given the above, your core focus will shift to building a subscription business. But in the first 1-3 years your dating service will be nearly worthless, as it will have to expand to different geographies and build up enough density to generate matches.

So you face a multi-year chasm where you won’t be making very much money, burning a lot of money, taxing unsuccessful users, while your customers are being plied from your grasp.

If you are an investor, you’d recognize this is taking on more risk than necessary to get an equivalent return elsewhere in the software world. The chance of success is markedly lower than that of any other regular software business.

Lack of Career Interest

Some of the smartest engineers & scientists in the world are in Silicon Valley. Relationships are among the most important things in our lives (especially romantic relationships). So why are we not obsessed with getting this right? Why are more brilliant people not working on this problem?

Highly technical people are generally uninterested in the touchy-feely aspects of relationships. They want to work on robotics, AI, and other things that are more tangible, easier to talk about.

In my personal contemplation of whether or not to work on this problem, I have come to realize that I feel the same way. I would rather work on a problem that is highly technical and concrete, that delves less into the vulnerable parts of ourselves.

People in Silicon Valley don’t want to talk about love, they want to talk about the next technological advancement that can get them an edge in a conversation. There is no professional power to be gained in being publicly vulnerable by working on helping people find love.

Diverting one’s career in traditional software engineering to found an online dating startup would be a significant risk. Even working for a new dating startup moves one’s career down a path they might not want to follow in a few years.

Above all, merely being interested in this problem space is a red flag. It brings about questions like “What’s wrong with that person? What could they not figure out that has them so interested in starting something new in dating? There must be something wrong with them.”

The other day I was at a party for a major software project’s launch, and when I explained to a male acquaintance that I was interested in working on this problem, he just looked at me deadpan and said ”Is there actually a problem?” (he was good looking & well connected, so I imagine did well online & offline)

When you have a problem where interest itself is taboo, and the most talented technologists won’t touch it, it would be hard to expect much innovation!

Most Jobs Are Done

Hinge is “the relationship app”, with intentional design choices (like making it a first-class UI concern to send a message on prompts or photos) made to slow down the user experience and make it more deliberate. Tinder is “the hookup app” (whether they want to call it that or not), with a much faster experience of rapidly swiping through photos (to the point only physical attraction is considered).

Each service fills some functional need people seek a solution for. American academic Clayton Christensen formalizes this in the Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) framework, stating that the unit on which to assess consumer choice is not their concrete demographics (age, race, gender, etc), but rather “jobs to be done” in their lives.

In a talk at Google[21] he says:

... I have all kinds of other characteristics and attributes, as you can see. But none of my characteristics or attributes have yet caused me to buy The New York Times today. There might be a correlation between the propensity that I will buy the The New York Times. But my characteristics don’t cause me to buy it. ... And yet, almost all of the work that we do in assessing market potential, we look at the characteristics or attributes of the potential customers. And a better way to think of [consumer choices], we decided, is that...darn it. Everyday, stuff happens to us. Jobs arise in our life. And when these jobs arise, we need to find some way to get the jobs done. And some of the jobs are simple incremental things that happen regularly. Others are dramatic and important breakthrough problems. But whenever we have a job to do, we have to find something and pull it into our lives in order to get the job done. And what we decided is understanding the job is the critical key to develop products that we can predictably make and find the customers to buy.

A mistake many creating new services will make is that they will propose incremental improvements to the user experience, without understanding the underlying job users are hiring them to solve.

There will be an initial influx of people who are looking to hire a service for the job of “Hinge & Bumble did not work for me, so I want to try out a 3rd app”. In the first year, tens of thousands will join in hopes that this new service will be somehow different for them.

But the adverse market dynamics that existed in other services will replay themselves in this new service over time. Even if the service somehow reaches a critical mass of users, the same systemic biases & hyperselectivity will arise once again.

Eventually users will start deciding to leave for existing services. Leaving to services like Hinge & Bumble, hoping that something will have changed in the time they were away.

And we will begin the cycle of “dating is broken” once again.

Moving the Problem Around

Some services will think they are solving a novel job users want to hire them for, but in reality they will just be moving the problem around without solving it.

A prominent dating app called “Soon” launched in San Francisco in 2023. The focus of the app was around getting users offline & going on dates in real life as soon as possible.

Dating apps around the time struggled to get users to be more intentional about setting up dates in real life. Instead, many DM conversations would drag on with neither participant taking much initiative to meet up in real life.

A flyer from Soon, mid-2023.

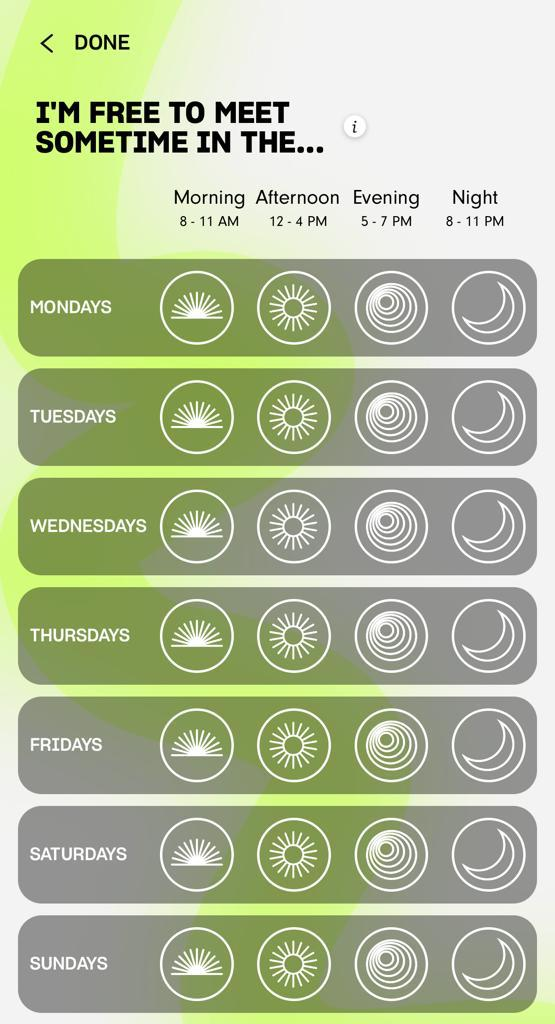

The app featured a schedule-on-match feature where matches would come with a time & place to meet up. Users would enter their availability beforehand.

Filling out your availability in Soon.

Early on, the app accumulated thousands in waitlist sign-ups. I was an early user of the app as well (only briefly using it). The organizers also hosted in-person events for users to meet each other offline.

Recently, I was talking to a female acquaintance who was using the app and she mentioned she had a bad experience. I always had a positive impression of the app (although I never went on a date through it), so I wondered what the hitch could have been.

She explained that on one occasion she matched with a guy who later while texting turned out not to be a great match. Upon matching, a time and place was already set for the date, and she didn’t want to cancel on him, so she went on the date anyway.

It turned out not to be a great fit, so she ended up on a 2 1/2 hour date with a guy she wasn't interested in.

While Soon solved the problem of intention in DMs, it created another by delaying the “vibe check” process, which also happens in DMs before a date. The selectivity, innate to the nature of the problem, just got moved further down the funnel.

Matchmaking Is Hard

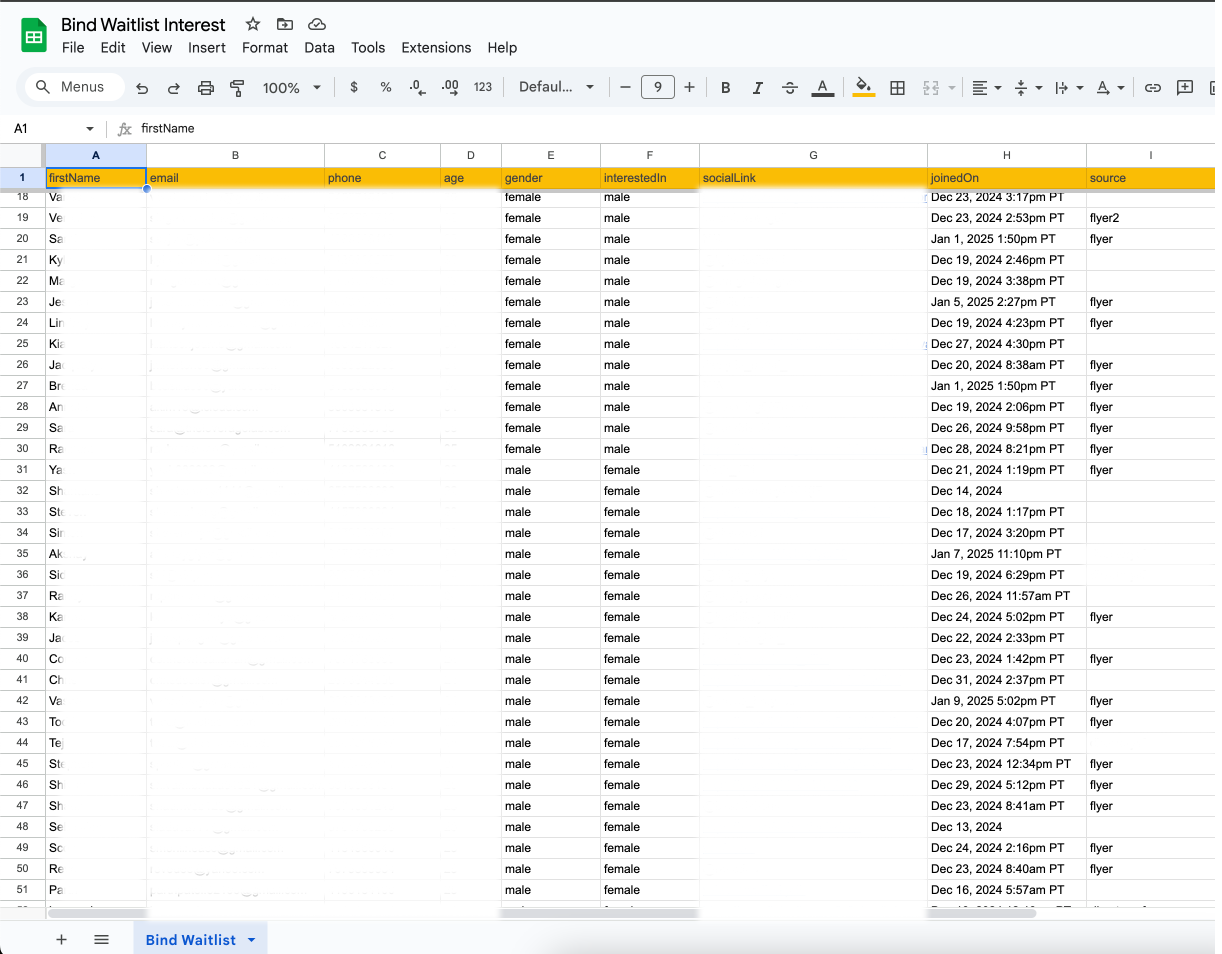

Making romantic matches is incredibly difficult. When I first launched the waitlist for Bind (link may or may not work), I got ~100 signups after about a week with the help of some flyers around the city.

~30 rows from the Bind waitlist.

I only collected basic information like age, gender, email, phone — and entries went into a Google Spreadsheet. Imagine the above, except 1,000,000 rows, and maybe 80 more columns, for various free-form and multiple choice survey questions.

This is the complexity matchmakers deal with. How do you decide who is a good match for who, while being fair to everyone? Can you “just use AI to matchmake”?

It must be harder than just looking for similarities to form responses with an LLM. There is a lot of information you wish you could collect as well. But all you have to go off of is what users have provided you.

The real bottleneck in solving the matching problem is relationship science. The underlying patterns we have to predict good romantic matches given discrete data points today is not strong (at least public research & literature I’ve read) enough to reliably predict variance in relationship outcomes.

The best way we have to beat the “market” is matchmaking based on “vibes”, using the eye of a (usually female) matchmaker who is sharp with people. With large general-purpose services, many otherwise matchable people fall through the cracks.

References

- Benson, John M., “The Public and Online Dating in 2024.” SSRS, 14 Feb. 2024, ssrs.com/insights/the-public-and-online-dating-in-2024/.

- Vogels, Emily A., and Colleen McClain. “Key Findings about Online Dating in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, 2 Feb. 2023, www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/02/02/key-findings-about-online-dating-in-the-u-s/.

- Lamb, Brad Albert and Hannah, and Stephanie T. Nguyen. “Monopolization Defined.” Federal Trade Commission, 4 Mar. 2022, www.ftc.gov/advice-guidance/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/single-firm-conduct/monopolization-defined.

- Harris, Larry. Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Thangavelu, Poonkulali. “Credit Card Market Share Statistics.” Bankrate, 7 July 2023, www.bankrate.com/credit-cards/news/credit-card-market-share-statistics.

- Buss, David M. The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating. 4th ed., Basic Books, 2016.

- Darren M. George, Dadria Lewis, Shayla Wilson, Jair Van Putten and Takudzwa Nengomasha (2023). The Direct and Mediated Influence of Perceptual Variables on Physical Attractiveness and Relational Satisfaction in Romantically Involved Heterosexual Couples. Psychology & Psychological Research International Journal. medwinpublishers.com/PPRIJ/the-direct-and-mediated-influence-of-perceptual-variables-on-physical-attractiveness-and-relational-satisfaction-in-romantically-involved-heterosexual-couples.pdf

- McNulty, J. K., Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2008). Beyond initial attraction: Physical attractiveness in newlywed marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 135–143. doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.135

- “David Buss: Sex, Dating, Relationships, and Sex Differences | Lex Fridman Podcast #282.” YouTube, Lex Fridman, 4 May 2022, youtu.be/sndW9hzX-wA?si=qKyey1sebz3pOz_7&t=1736.

- Fugere, Madeleine & Chabot, Caitlynn & Doucette, Kaitlyn & Cousins, Alita. (2017). The Importance of Physical Attractiveness to the Mate Choices of Women and Their Mothers. Evolutionary Psychological Science. 3. 10.1007/s40806-017-0092-x.

- “Hinge’s Makeover: The New Era For Dating Apps.” YouTube, CNBC Make It, 31 Jan. 2024, youtu.be/MC4WRNAv1bg?si=hG8sKEY0omnPTY2V&t=291.

- Covington, Paul, et al. Deep Neural Networks for YouTube Recommendations, Google Research, 7 Sept. 2016, static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/45530.pdf.

- Brecht Neyt, et al. “Are Men Intimidated by Highly Educated Women? Undercover on Tinder.” Economics of Education Review, Pergamon, 22 July 2019, sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272775719301104.

- Florio, Gina. “Only 15% of Women Show Interest in 5’8" Men on Dating Apps, According to Survey.” Evie Magazine, https://www.datocms-assets.com/109366/1698967220-evie-logo.png, 6 Nov. 2023, eviemagazine.com/post/only-15-women-interest-58-men-dating-apps-according-survey.

- (tbd)

- “Bumble’s Herd on the Next Chapter of Growth.” YouTube, Bloomberg Live, 5 May 2024, youtu.be/Y95T58DSREU?si=GMHrvxuu-tXlphaE&t=239.

- What’s Driving Dating App Fatigue In 2024—And What Relationship Experts Want You To Do About It, Women’s Health, 12 Sept. 2024, womenshealthmag.com/relationships/a62081332/dating-app-fatigue-burnout/.

- “Hinge Tests Limiting Unanswered Messages to Reduce Dating Burnout.” Hinge, 14 May 2024, hinge.co/press/your-turn-limits-test.

- Rubin, Rick, and Neil Strauss. The Creative Act: A Way of Being. Penguin Press, 2023.

- “Where Does Growth Come From? | Clayton Christensen | Talks at Google.” YouTube, Talks at Google, 8 Aug. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHdS_4GsKmg.